The acquisition of coveted artwork and luxury items, such as wine, jewelry, and collectors’ cars, can be exhilarating. However, these purchases are accompanied by high risks. Whether the items are forged or previously stolen, accompanied by inaccurate valuations, or in a different condition than represented, collecting is fraught by pitfalls.

Luxury goods have long been a staple of the art market, and they are hallmarks for wealthy collectors. Art and collectible wealth were valued at an estimated $1.742 trillion as of 2018, with Deloitte analysts predicting (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) the potential to reach $2.125 trillion by 2023. While collecting can be a rewarding experience, it is not without hazards.

As with art collectors, buyers of luxury goods fall victim to forgeries – and wine is no exception. High ticket-priced items are a target for enterprising forgers who capitalize on the demand for rare objects and purchasers’ blind spots. Forgers may even fabricate provenances, at times including illustrious former owners. A recent example includes “Venus,” a painting said to be the work of Renaissance artist Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Although the work was part of the Prince of Liechtenstein’s private collection, its provenance did not save it. It was purchased from an Old Masters forgery ring, and was not painted by the German Old Master painter, but by modern master forger Wolfgang Beltracchi, whose fraudulent pieces fooled art experts for years. Charles, Prince of Wales also fell victim to forgers when his charity displayed £105 million worth of forged art.

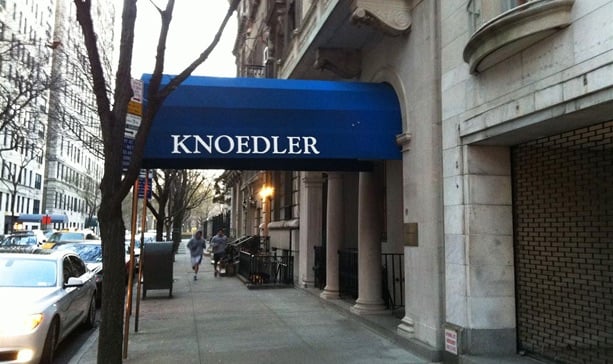

Knoedler case

Another shocking forgery scandal involved a leading Manhattan art gallery, the Knoedler Gallery. Knoedler traces its origins to 1846, when French dealers opened a gallery branch in New York. During its years selling art to major collectors, the gallery earned a stellar reputation, selling notable works to well-known collectors. However, the prominent institution was brought down by a scandal that involved the sale of multi-million dollar forgeries that were painted by a poor immigrant working out of a garage in Queens, New York.

Rather than conducting due diligence, collectors eagerly acquired artwork based upon the Knoedler Gallery’s premier reputation. (In one case, a collector even purchased a painting in which the forger misspelled the name of the artist in the signature.) As a result, collectors were limited to pursuing costly litigation and accepting settlement payments after the gallery shuttered its doors the day following the forgery’s revelation.

Like collectors who rely upon a gallery’s reputation, some buyers are lured into purchases after being charmed by charismatic sellers. Collectors may be encouraged to purchase forged works after developing close relationships with unscrupulous dealers. Dealer Ronald Safdieh enticed a married couple into purchasing $400,000 of Russian collectibles, including a Fabergé egg that later turned out to be a forgery. The dealer not only concocted an elaborate backstory, but he also issued a certificate of authenticity and a buy-back guarantee. Unfortunately for the buyers, Safdieh had already been sued twice for the alleged sale of fake Russian antiques.

Wine forgery

To successfully commit a forgery scheme, a con artist must win his victim’s trust – this is an essential part of the scam. One of the largest wine frauds in history involved young wine connoisseur Rudy Kurniawan. He charmed his way to the top of the wine industry and convinced collectors that he was a reliable source for rare and valuable vintages. Gifted with a delicate manner and a sommelier’s palate, Kurniawan set up a wine laboratory in his home where he brewed his own batches of dupes and sold them to unsuspecting collectors through legitimate auction sales. Kurniawan claimed that his bottles were old vintages belonging to other collectors. The considerable value of the bottles was partially based on their incredible provenance, along with their condition and rarity. Kurniawan was a true forgery artist – he repurposed old bottles, imitated the texture of specific corks, used similar wax seals, and artificially aged labels so that his creations looked, smelled, and tasted like the real thing. Although the scheme was relatively simple,

Kurniawan’s confidence and insider knowledge allowed him to fool a significant number of people in the wine industry, many of whom are experts in the field. The bottles’ sham histories allowed the con artist to sell the bottles for tens of thousands of dollars. One bottle consigned to Christie’s sold for $56,000 after Kurniawan claimed that it had belonged to former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson. In 2006, Kurniawan sold an astounding $24.7 million worth of counterfeit wine at the reputable auction house of Acker Merrall & Condit.

Eventually, Kurniawan upset the wrong man. His luck ran out when he was sued by prominent businessman William I. Koch. Koch had become suspicious when a large number of rare wine bottles began appearing on the market. He hired a private investigator to unravel the fraud. Koch, a man of incredible financial means, sued Kurniawan in federal court in New York. The businessman pursued Kurniawan until the scheme was exposed, and the forger was ultimately arrested in March 2012. Kurniawan was sentenced to ten years in prison. The exact amount the con artist extracted from his victims is unknown, although the latest estimates place it at a staggering $550 million.

While Kurniawan’s scheme was unveiled and he was sent to jail, wine fraud does not end with him. Wine fraud schemes can take many forms. It has become a billion-dollar problem worldwide, and like buyers of art or luxury goods, it is important for all wine collectors to perform due diligence. Purchasing directly from producers or certified vendors might be relatively safe; however, secondary market sellers, such as auctions, retailers, and brokers, is another matter. Counterfeits range from refilling authentic wine bottles to making imaginary vintages, all the while preying on inexperienced collectors. However, even players that have participated in the market for many years are still at risk if the forgery scheme is as deceitful as Kurniawan’s.

Damaged wines

Another fraudulent scheme is the sale of wines and spirits marred by floods or fires. Even when salvage and insurance companies disclose damage, sellers maximize value by withholding material information during subsequent transactions. After Hurricane Katrina, the market was flooded with high-end wine that appeared drinkable; in fact, they had a very short shelf life and were not as robust as represented. Sellers failed to disclose that the bottles were damaged. This type of fraud is rampant, particularly as profiteers dump damaged wines on emerging markets. Also, counterfeit bottles have a tendency to end up back in circulation. The bottles counterfeited and sold by Kurniawan, for example, are still being resold on the market. These forged bottles could have quadrupled in value since the con man’s imprisonment, providing an incentive for fraudsters to continue selling them. Meanwhile, sophisticated new counterfeiters are targeting mid-range wines and recent vintages to sidestep scrutiny.

Wine frauds involve exorbitant amounts of money, so why aren’t they prosecuted more frequently? Victims of wine fraud, like victims of art fraud, often feel shame for falling prey to a scam. Fearing public exposure and scrutiny, they refuse to come forward to file civil cases against schemers or report the crimes to law enforcement. Previously, the FBI had a dedicated agent assigned specifically to wine fraud cases, but the bureau determined it was a waste of resources since they could not depend on the victims’ cooperation.

Experts help

Despite the lack of legal actions for wine fraud, a few alternative remedies remain for consumers. First, online resources, such as www.winefraud.com, allow potential buyers to educate themselves and verify whether particular sellers are blacklisted. These are similar to stolen art databases that provide collectors with information to ascertain whether their purchases were stolen or went missing. Second, the role of an authenticator, as in fine arts and antiquities cases, is invaluable. Experts are hired to verify the ownership history (the provenance) of bottles and confirm the existence of particular vintages and labels. Forensics experts also have a role. These scientists can conduct age tests on corks, papers and inks used on labels, or even the wine itself. Consulting with experts mitigates the risk of falling victim to wine fraud, allowing purchasers to ensure that they are buying the real thing. After all, “AUTHENTICATING A WINE IS LIKE AUTHENTICATING A WORK OF ART.”

Legal protection

Falling victim to wine or art fraud can be a costly ordeal that is damaging to professional reputations. With this in mind, it is important for collectors to engage a qualified legal team to assist with vetting an authenticator and facilitating the purchase process in its entirety. Law firms are retained to provide valuable legal protections in the form of purchase and sales agreements and other documentation that allow collectors to recover funds, in the event that their acquisitions are revealed as stolen, forged, or in poor condition. Amineddoleh & Associates has a robust network of experts in all facets of the transactional process, as well as a history of guiding collectors through the acquisition of artwork and luxury goods, thereby providing clients with the peace of mind to not only collect their wine, but enjoy it too.

Art & Wine Magazine thanks Amineddoleh & Associates for the interesting insights and helpful tips on how to protect your art and wine investments.